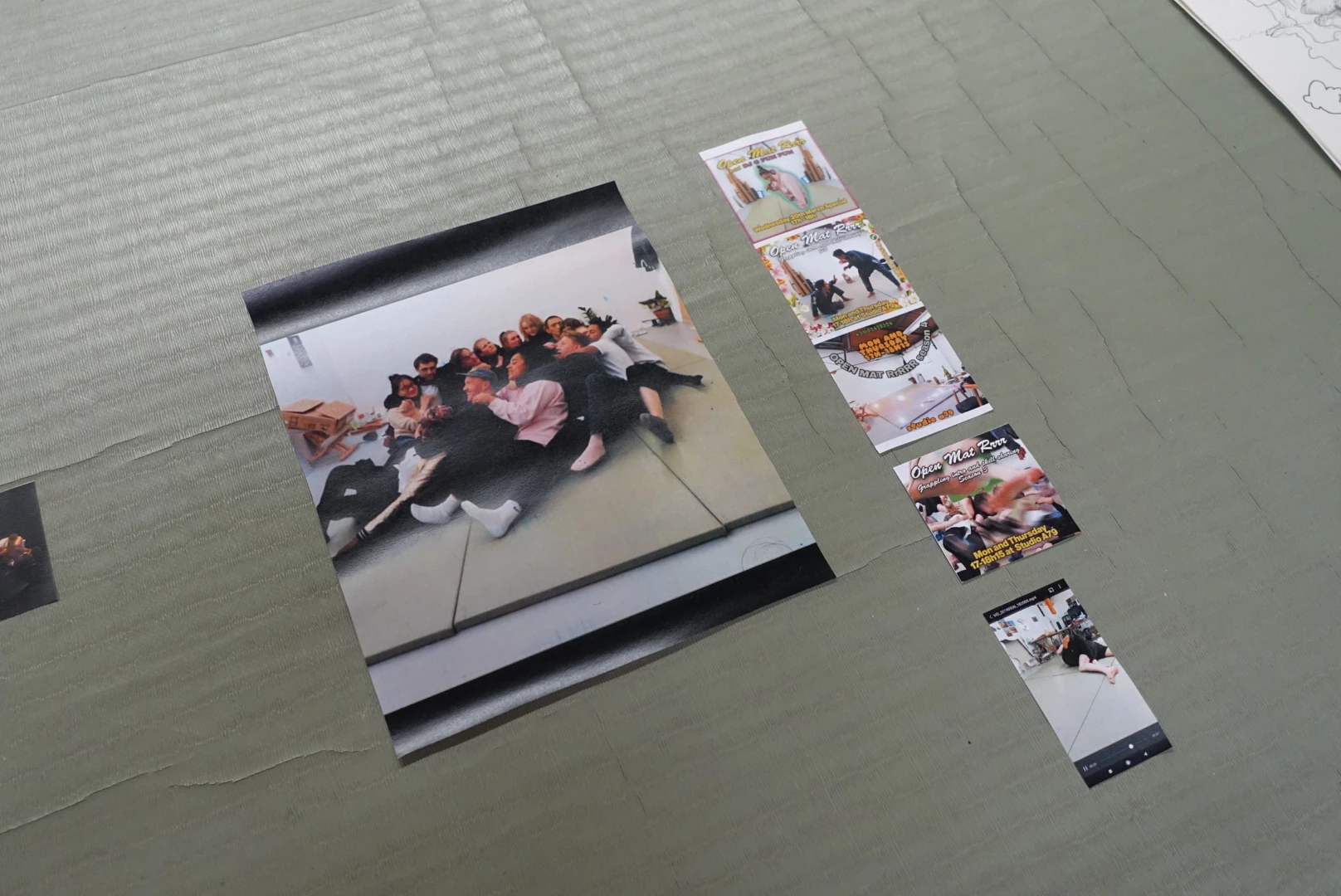

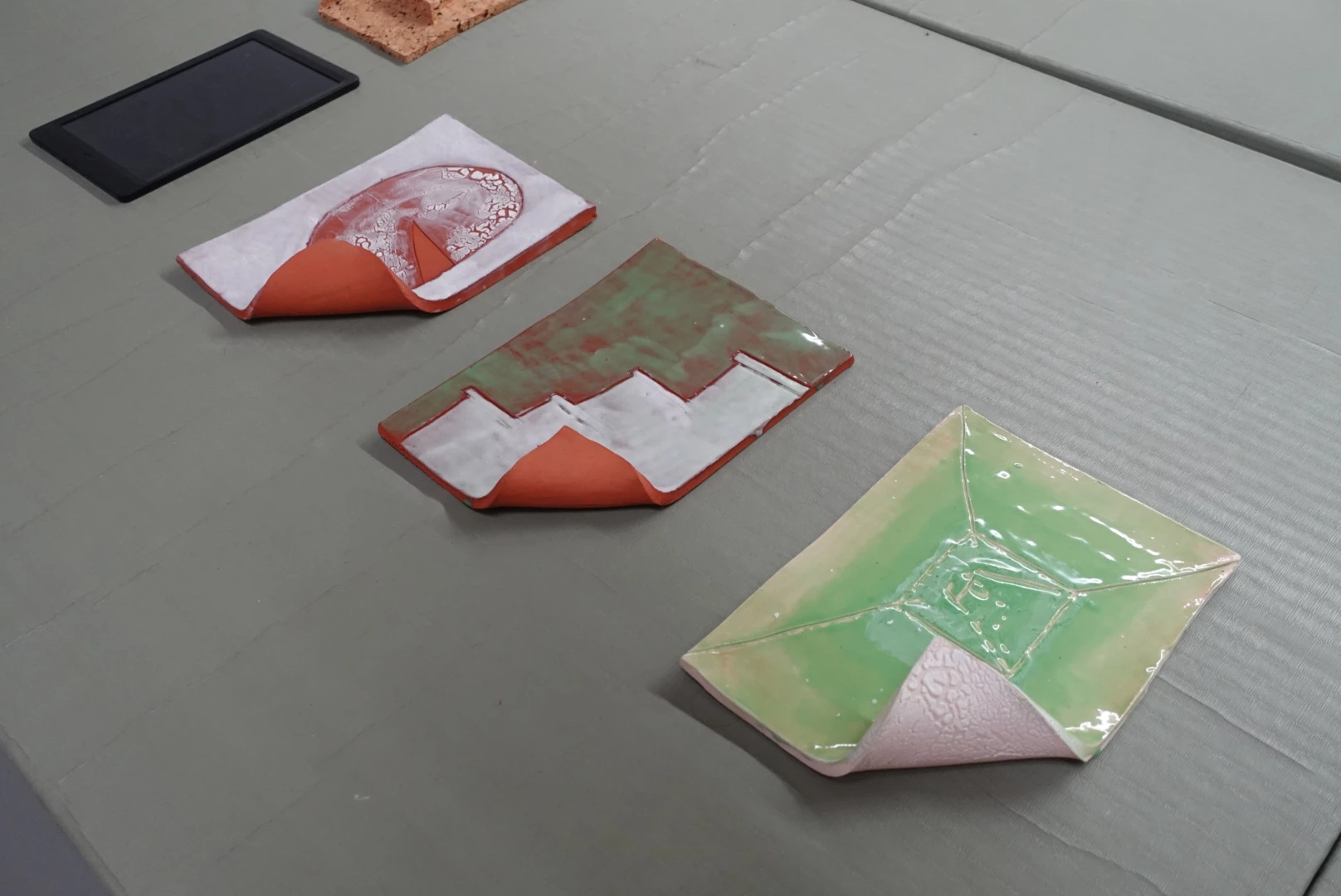

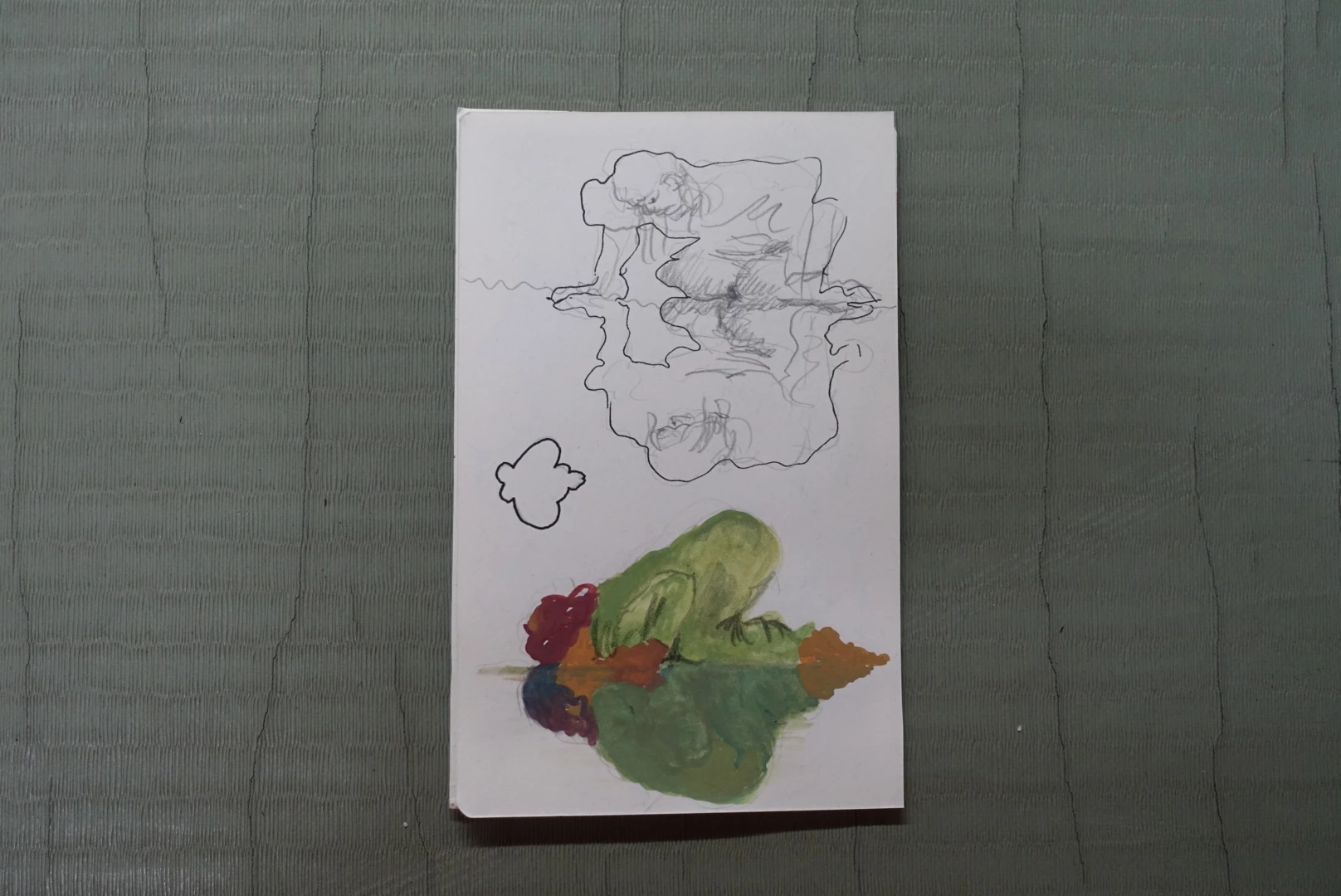

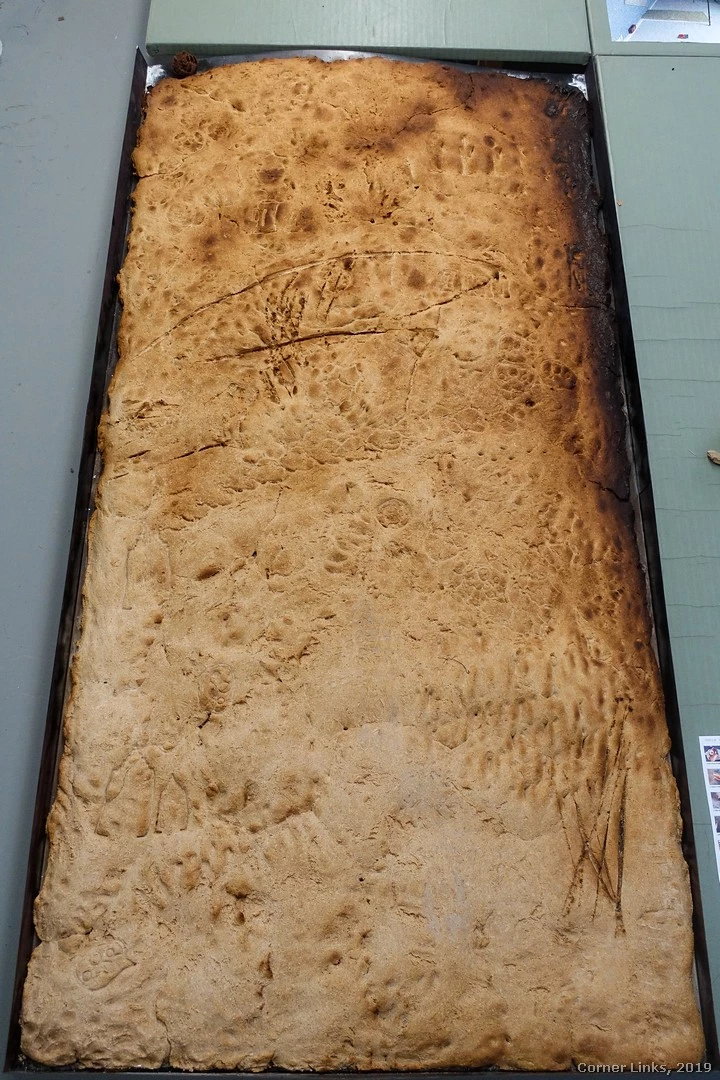

Corner Links is a performance work emergent from a year-long process of Bayri’s experiments with how to embody his negotiations with power structures (national, cultural, artistic). It was first performed at the 2019 Rijksakademie Open Studios where the artist’s studio space was transformed into an installation comprised of a table made with tatami mats and trestles; a selection of artifacts made by the artist, including ceramic tagines, guache drawings, digital collages, and oversized breads; a television monitor featuring graphics, small animations and short videos; and an elevated desk in the corner, where Bayri periodically sat.

One of the most layered and durational experiments that the artist has thus far embarked upon, the piece has three key coordinates: the constant flow and unpredictability of the chat platform Paltalk, the push and pull of the Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu lesson, and the date 20 November. Arriving in Amsterdam in 2018, Bayri found himself at a crossroads, reflecting on his personal relation to Islam and the Moroccan state, as well as the monastic environment of the self-enclosed studio practice at the Rijksakademie. In time, a routine developed which saw Bayri moving through his days with earbuds in as he listened to the taboo-free stream of chatter in the Paltalk rooms “Moroccans in and outside of the country” and “Moroccans for a secular country”. Parallel to this, Bayri also set up tatami mats at his Rijksakademie studio (the same mats that would later become a stage in his performance) where he began giving Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu twice a week. On the mats, the ‘grappling’ that was unfolding in the Paltalk rooms took on an embodied form. Eventually, after months of this routine, the two practices came together in Corner Links, which transformed this ‘grappling’ into a mode of non-linear storytelling. Sitting at the elevated corner desk, Bayri told a story centred around the date 20 November – the day the Siege of Mecca began in 1979, which was 40 years to the day before the artist’s performance began. This story, though, it moved around. It loopily wriggled through time and space, transforming the artist’s handmade tagines into characters and his oversized breads into a topography of chance encounters. As the storyline jumped, so too did Bayri’s voice as narrator, which improvisationally drifted, like chatter, between the calm authority of the tennis referee, the righteous resound of the preacher and the tired friendliness of the call centre worker. In its surrealistic twists and turns, the performance undid the terms of narration, pushing “non-linear storytelling” to its absurdist capacities and inviting the audience to laugh (and laugh they did) at the jumble of information held together in any one story. In turn, for Bayri, reading (of texts, objects, images, histories and even the self) became an act unfolding in its doing; an act of staying present, agile and aware.